Teaching your kids about money

Where money is concerned, Larry Smith and his wife, Cynthia,

have tried to set a good example for their three children.

Though they own a spacious home and like to travel, the Aptos, CA, couple have eschewed

luxury cars, designer clothes, and other high-life frills. They seldom buy on impulse,

they pay off their credit cards each month, and they carry relatively little debt. Those

money-wise habits appear to have rubbed off on their 13- and 10-year-old sons, both ardent

savers.

It's a different story with their I6-year-old daughter. "No matter what we've

tried, money has always run through her fingers," says Cynthia, who's convinced that

genes have a greater influence than upbringing on a child's approach to money.

Many experts say that because of genes and upbringing, your kids' money behavior

probably will mimic your own. Since you can't do anything about their genes, your best

shot for helping them become financially responsible is to teach good money habits and

practice what you preach. As the Smiths' experience shows, you might not be 100 percent

successful-but two out of three money-smart kids ain't bad.

In 1997, a survey sponsored by the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy,

a nonprofit organization, found that most high-school seniors knew little about personal

finance. On a multiple-choice test that covered credit-card use, taxes, savings, and the

like, the teens answered only 57 percent of the questions correctly, on average.

That may well reflect an absence of solid financial teaching in the home. "Many

parents just don't talk about money," says Carol Wilson, a financial adviser in Salt

Lake City. "It's hard for kids to become good money managers if no one has taught

them how."

Feed your preschooler some money basics

Wilson and others recommend an early start for money talk between parents and children.

Your toddler begins learning about money from what she observes during visits to the

store. When she reaches age 3 or 4, you should be explaining some of your shopping

decisions: 'We're buying peaches today because they're on sale," or "We're using

coupons from the newspaper to help pay for our cereal."

Let your child help you put items into the cart and unload them at the checkout

counter. If he's always asking you to buy him a treat, give him a small amount of money

each week (a dollar is enough, says Wilson) to make his own purchase. Direct him toward

appropriate items he can afford. Then let him give the money to the cashier and receive

the change. Even if he can't count beyond 5 or 10 at this point, he'll begin to understand

how money works.

At home, teach your preschooler to distinguish among pennies, nickels, dimes, and

quarters, and explain that each has a different value. Empty a coin purse on the floor and

help her sort the coins into piles. Tell her how many of each kind adds up to a dollar.

(She may be surprised to learn that a dime is worth more than a nickel, even though the

nickel is bigger.) To reinforce the lesson, play "store" with your child, using

her toys as "merchandise" and your spare change for payment.

Don't be surprised if she asks where the family's money comes from. If possible, take

her to your medical office (or your spouse's workplace) and explain that you receive money

for the work you do there. Even if you enjoy a six-figure income (information you probably

shouldn't share with her yet), let her know that the family's money supply is limited and

should be spent carefully.

Use an allowance to help your Child plan for expenses

By the time your youngster enters elementary school, he'll probably be lobbying for an

allowance. Don't buy the argument, "All the other kids get one." According to a

poll by Zillions, a children's magazine, only 43 per cent of 8- to 14-year-olds get an

allowance. Another survey, by the authors of "The Kids' Allowance Book," showed

that half of the youngsters in families it sampled got money for chores, birthdays, and

holidays-or just by asking for it.

Kids who aren't on allowance don't have consistent income; it's difficult for them to

set goals, budget, and save, because they don't know how much money they'll have each week

or month. In fact, kids who get allowances do tend to save more, a recent Zillions survey

found.

"An allowance is an excellent money-management teaching tool," says Carol

Wilson. "Young children can be taught to save and budget for things they want to buy

next week or next month. As they get older, they can work toward bigger financial goals,

such as buying a car or subsidizing college costs."

Experts differ on when to start an allowance, how much to pay, and whether your kids

should earn income by doing chores. Neale S. Godfrey, author of "Money Doesn't Grow

on Trees" and "A Penny Saved," recommends an allowance as early as age 3.

She believes children should receive a dollar for each year of age and be taught to

apportion their money for spending and short and long-term saving. Godfrey also thinks

allowances should be tied to chores, so that children see the connection between work and

money.

Patricia Schiff Estess and Irving Barocas, authors of "Kids, Money &

Values," say that by the time a child enters elementary school, he should start

getting an allowance "large enough so some of it can be saved." They caution

against linking the allowance to "chores, love, approval, punishment, and

reward." An allowance has only two purposes: to help a youngster learn to manage

money, and to let him share in the family's resources. Surveys show, nevertheless, that

most parents who give allowances do tie them to chores.

How much allowance? One recent survey showed that youngsters age 8 to 9 average about

$4 a week, while 10- to I 1-year-olds get about $5, and kids 12 to 14 receive $7 to $9

weekly. Many teens supplement allowance income with earnings from extra chores or

part-time jobs. Parents can foster the idea of extra pay for extra work by posting a list

of special chores, with proposed fees.

To calculate an allowance, start with the expenses it must cover. Young kids might be

required to pay only for treats; as they get older, you might have them budget for such

things as school lunches, movie tickets, clothes, and transportation. A fair allowance

should be enough to cover "needs," with a reasonable amount left over for

"wants." (You and the child will have to negotiate the definition of

"reasonable.")

At some point, your grade-schooler is likely to blow some or all of her money. Janet

Bodnar, author of "Dr. Tightwad's MoneySmart Kids," offers a rule of thumb:

Don't give more than you can stand to see your kid squander. Though the child needs enough

freedom to make money mistakes and learn from them, don't hesitate to restrict spending on

anything you deem unhealthy or inappropriate.

Another challenge you're sure to encounter: what to do when

your kid asks for an advance. just say No, Carol Wilson advises. "She has to learn to

anticipate needs-and to experience the consequences if she doesn't," says the

planner. Other experts say advances can be appropriate under special circumstances, but

not on a regular basis.

Have your teen try on a clothing budget

Family physician Bob Jones and his wife, Lorraine, have seen firsthand how allowances

can teach kids about money. When each of their two daughters turned 13, the Joness

established a clothing allowance. Based on spending histories, the Scottsdale, AZ, couple

determined how much each girl should be permitted to pay for clothes for a year. 'We took

them to the bank to open checking accounts," says Bob. "Then we deposited

onetwelfth of each one's clothing allotment into her account each month."

The daughters had to budget for all their clothes, and balance their checkbooks.

"If they messed up, we wouldn't bail them out," says Jones. He recalls one

bounced check and a winter when one daughter did without a warm coat-a hardship, since the

family lived in Wyoming at the time. To keep their money responsibilities from seeming too

onerous, each girl received a separate allowance-$1 per grade level in school-for

discretionary spending.

When each daughter turned 16, her clothing allowance was expanded to include all

personal items. At this point, the Joness also provided each girl with a $3,000 used car

(titled in the parents' names) and picked up the insurance costs. But the youngsters first

had to qualify for the insurer's good-grade discount and agree to buy the gas for any

non-essential driving.

"Things have worked out really well," says Bob Jones.

"Our girls became thrifty. They scouted out clothing sales and cruised thrift stores.

We listened at the end of each year if they pleaded for more money, but we never had to

increase their allowance by much."

The Joness' daughters are now 19 and 16. The older saved paychecks from her summer job

to buy a computer for college. Her sister, a high-school junior, will save her allowance

"like a skinflint," says father Bob, to pay for a plane ticket to visit a

friend. Jones is satisfied that his daughters have become responsible about money. "I

didn't want them growing up thinking it grows on trees," he says.

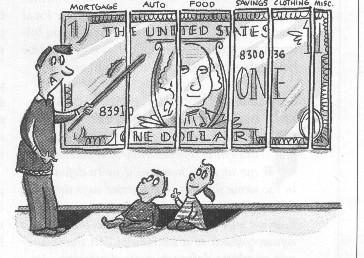

Get your youngster in touch with the family’s finances

In addition to teaching your child to be prudent with his money,

share with him often how you're running your finances.

When he's old enough (by middle school), explain that your income is divvied among

living expenses, investments, your retirement plan, his college fund, and other

obligations. Tell him how you're planning ahead for the cost of next summer's family

vacation and the dream house you want to build in five years. Don't emphasize how much you

have, but rather that you must manage your money wisely to meet financial goals.

For some hands-on experience, let your youngster help with paying bills. Though he

can't sign the checks, he can write in the amounts and prepare the envelopes. Be sure to

show him your credit-card bill, explaining how much extra you'll owe if you don't pay it

off each month. Exposure to your financial responsibilities will help him see the need to

hone his own fiscal skills.

Ideally, by the time your youngster reaches high school, he'll already have a bank

account and will understand principal and interest. If he's really money-smart, he may be

investing on his own, perhaps in a youth oriented mutual fund. (One example is the no-load

Stein Roe Young Investor Fund, which has a minimum initial purchase of $2,500.) By the

time he graduates from high school, he ought to know how to balance a checkbook, budget

and save, and avoid credit-card debt.

Unfortunately, many young people don't know these things. Naive college students, for

example, are easy prey for card issuers. If you've been unable to teach your teen these

money-management basics yourself, you may need outside help. Many of financial adviser

Carol Wilson's physician clients have sent their 17- and 18-year-olds to her for

counseling.

Fewer kids would need her services, Wilson believes, if parents would make them get

part-time jobs and resist the temptation to give them too much. 'Jobs give kids a sense of accomplishment and expose them to financial

realities such as paycheck withholdings and income taxes," says Wilson. "Young

teens can start with odd jobs such as babysitting or lawn care, and move up to jobs with

an hourly wage as they get older."

Want to know more?

For more on teaching kids about money, see:

"Dr. Tightwad's Money-Smart Kids," by Janet Bodnar

(Kiplinger Books, 1997).

"Money Doesn't Grow on Trees," by Neale S Godfrey (Fireside-Simon &

Schuster, 1994).

"A Penny Saved," by Neale S. Godfrey (Fireside-Simon & Schuster,

1995).

"Kids, Money & Values," by Patricia Schiff Estess and Irving Barocas

(Betterway Books, 1994).

"The Kids' Allowance Book," by Amy Nathan (Walker and Co., 1998).

|